Church of St Andrew, Sutton-in-the-Isle, Cambridgeshire

Address

Church of St Andrew, High St, Sutton, Ely CB6 2RHTheme

Overview

Lawrence Lee (1909 – 2011) was one of the most distinguished stained glass artists of the 20th century. It is not surprising therefore that a number of contributors chose to include one of his windows in their selections. But there is much more to say and to celebrate about this wonderful artist.

A Theme has therefore been dedicated to the work of Lawrence Lee. The windows highlighted within the Theme have been chosen in conjunction with his son, Stephen Lee, to highlight some of his father’s best work.

A full list of the windows chosen can be found by following the link above. There you will also find two papers written by one of his former assistants, Philippa Martin, covering his life and his most famous achievement, the masterminding of the ten nave windows of Coventry Cathedral.

Highlight

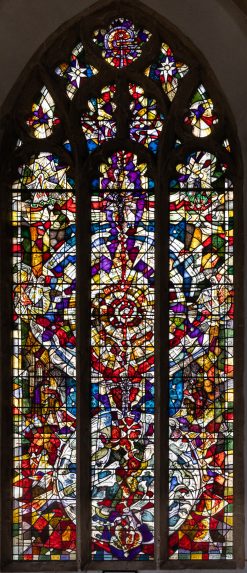

Chancel south windowArtist, maker and date

Lawrence Lee, 1975Reason for highlighting

As noted above, this window is one of a selection made in conjunction with Lawrence Lee’s son, Stephen Lee.

The following description of the window is by Lawrence Lee

I hope that parishioners and visitors alike may be helped by a few guide-lines on the concept of the window and then, forgetting what I have written, develop their own thoughts – preferably by looking at it alone and in quietness.

It must be made clear that the window is not abstract, if by abstract we mean something without representation of any recognisable object or subject. The fundamental scale, structure and image are traditional: the framing of the borders and the repeated vertical lines, bound by horizontals at intervals, form a scaffold on which the main subjects are developed – in accordance with medieval principles of design. This structure might be called abstract in a mathematical sort of way, and as such is one of the elements of abstraction that must be present in a window that is true to its intrinsic relationship with the architecture that provides its frame. Stained glass is an extension of the wall – not merely a transparent religious picture.

In looking at the window may I ask that you think of your observation as much a part of worship as taking part in the words and music of the Liturgy, for this is its proper function. Don’t bother too much about the aesthetics. In essence art is a religious activity, a traffic between non-material ideas and their expression in material work.; in art devoted to the religion of the Incarnation this double reality has a special significance, justified by a sanction not normally understood by art critics.

This traffic between God and man; how is it expressed in visual terms? In music it may be through a simple hymn or a great Mass; “Cwn Rhondda” sung in Welsh, Bach’s B Minor Mass sung in German, both making sounds in a language we may not understand, yet making some deep communication to the mind and spirit that needs no words. The Chancel window, by virtue of its great size, cannot be a simple hymn, but rather it calls for a statement, development and conclusion that is more akin to a symphony. This then is a convenient point from which to discuss the theme of the window.

Simply stated the theme is man ascending and God descending, and meeting at a point where both are mysteriously involved in a universal energy. I have returned to symbols used by primitive man to express this – the Y shape with its arms pointing upwards (in red) and the same shape inverted (in purple) link with each other to embrace a centre of energy which itself moves out centrifugally to be dispersed into the ascending movements of the side lights, and rises to a final resolution in the topmost tracery.

In our day we have been singularly blessed with a new image of our Earth, given us by the men who travelled to the moon. Seen from space, our earth is now revealed as unexpectedly beautiful – a blue world serene in a lonely galaxy of the universe. It seemed the ideal starting point from which the ascending motif of the design should begin. It is not however a literal representation, but shown as cooling from the molten state, forming an atmosphere and laying down the elements from which came life.

From this embryo, rising shapes gradually form into the symbol of a man at a point where the movement upwards reaches an area where the two realities meet. On each side of the forming earth, shapes that vaguely suggest angels may be detected growing from the fiery space around them (“…He maketh His angels spirits and His ministers a flame of fire…”). At the linking of the main Y symbols, they reappear in a more recognisable form – and incidentally help to control the swirling movement from breaking out of the frame.

At the springing of the arch the cross motif is quire distinct, spreading from the reappearing figure of man – “slain from the foundation of the world”. Again, the ends of the cross are stopped by symbolic representations: on the left a pelican in her piety (charity), and on the right by the sun, clouds, rain and growing shoots (the source of life on the earth).

The donor wishes that I might include some reference to the support of many charities that his family undertook, and also to their background of farming stock. These things I have incorporated at the level between earth and the central motif. On the left a woman holds under her cloak a child, against a background of ruined buildings and wintery trees; while on the right the figure of a farmer tending his fields in a rural background may be seen as a simple pastoral subject.

The English letter G, being the initial letter for God is interesting. A universal emblem for eternity is a circle – complete, having no beginning or end; but the letter G is a broken circle – an incomplete figure needing but a stroke to make it a circle once more. The topmost tracery light is a play on this idea, combined with a representation of the central whorl as the serifs of the G turn in on themselves; at the place where the circle is broken there is a dot – Man’s soul growing to complete the circle?….

Stephen Lee adds that it worth seeing his father’s window at the Church of St Giles, Matlock, for an earlier exploration of a similar design idea.

Artist/maker notes

Lawrence Stanley Lee FMGP (1909 – 2011) trained at Kingston Art School and the Royal College of Art before the war. After the war he worked for Martin Travers, and it was Travers’ unexpected death in 1948, which led to Lee forming his own studio. A wide range of commissions followed, including his famous windows at Coventry Cathedral, with Keith New and Geoffrey Clarke, which established his reputation. Lee was also a teacher both formally at the Royal College of Art, and in his studio to a succession of assistants. He was notable in acknowledging the contribution of his assistants by including their initials on windows, along with his own.

Other comments

Lawrence Lee was assisted in the making of the window by Janet Christopherson.