Church of St James, Milton, Southsea, Portsmouth, Hampshire

Address

Church of St James, 285-287 Milton Road, Southsea, Hampshire PO4 8PGTheme

Overview

Lawrence Lee (1909 – 2011) was one of the most distinguished stained glass artists of the 20th century. It is not surprising therefore that a number of contributors chose to include one of his windows in their selections. But there is much more to say and to celebrate about this wonderful artist.

A Theme has therefore been dedicated to the work of Lawrence Lee. The windows highlighted within the Theme have been chosen in conjunction with his son, Stephen Lee, to highlight some of his father’s best work.

A full list of the windows chosen can be found by following the link above. There you will also find two papers written by one of his former assistants, Philippa Martin, covering his life and his most famous achievement, the masterminding of the ten nave windows of Coventry Cathedral.

Highlight

South wall window of the St Cross ChapelArtist, maker and date

Lawrence Lee, 1967Reason for highlighting

As noted above, this window is one of a selection made in conjunction with Lawrence Lee’s son, Stephen Lee.

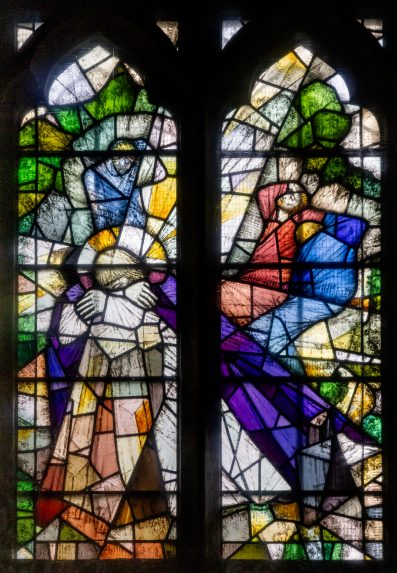

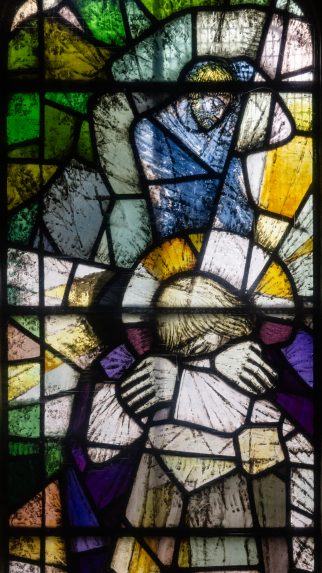

The subject is the Passion, not symbolised by the crucifixion, but by the agony of will in the Garden of Gethsemane. The figure of Christ in prayer is shown as the pivot of a superhuman cross motif – literally at the crux of the matter. There is a soul of cataclysmic break-up all around, and great tension in the hands, but also a point of stillness of which T.S. Eliot speaks. The sleeping disciples symbolize the utter removal of all human aid; they also by their positions help the centrifugal movement of the whole design.

Stephen Lee adds

This subject has been treated by the old masters, usually with Jesus in the conventional prayer position – kneeling, hands and eyes upraised to heaven; perhaps receiving the Chalice from an angel, perhaps with the soldiers approaching to arrest him. Here the artist chooses an earlier time in the drama, with Jesus at his lowest point when he knows he will be betrayed, captured, and put to death. He is mortally afraid (the power of this god lies in his assumption of very human emotions), and his will falters.

This is the third time Lawrence Lee used the image of Jesus with his head buried in his hands. The first instance in in the West Window at All Saints in Ryde, 1952 (less than 5 minutes’ walk from my house!), and the second in one of the ten great windows in Ss Andrew and Paul, Montreal, 1963. Here it is more fully exploited by combining it with a visual representation of a metaphysical idea expressed in Eliot’s Burnt Norton.

The particular passage he had in mind is from Part II of this poem, beginning “At the still point of the turning world” and the whole passage, if not the whole poem, is relevant to this window. Eliot gives a poetic explanation of the Buddhist conception of the point between past and future (where time does not exist), between motion and stasis (“between two waves of the sea”), and between thought and absence of thought (meditation).

Lawrence Lee does the same in visual terms. What he has done is to introduce movement into an essentially static situation – all four figures are completely still and the design has to suggest movement in order to locate the still point. This movement is the interior agony experienced by Jesus, and is expressed by the tension in his body and the whirling of the world about him.

The window shows us that this “centrifugal movement” is centred on a still point (as it must be – think of a wheel turning on its axle) and that this point is centred in the body of Christ. The finding of this still point will lead to his acceptance of his chosen fate.

Lawrence Lee’s method, as was becoming common around this time (1967), was to fuse abstract and figurative elements – there are heads and hands, but bodies, cloaks, and the garden foliage are not treated naturalistically, and much of the background is pattern only (and there the dance is”).

The still point is also the centre of the cross, which although it foreshadows the angle at which Jesus will carry it on the road to Calvary, is an image (a motif) only and has no actual existence. It is a cross of light, and the arm which reaches down from top right to bottom left can easily be read as a beam of sunlight breaking through the gloom, an image which also plays a pivotal role in Eliot’s poem (“sudden in a shaft of sunlight”).

It occurs to me that since all circular motion must be centred on a still point, so the Universe must have such a centre. There is nothing there, but we might call it god.

Artist/maker notes

Lawrence Stanley Lee FMGP (1909 – 2011) trained at Kingston Art School and the Royal College of Art before the war. After the war he worked for Martin Travers, and it was Travers’ unexpected death in 1948, which led to Lee forming his own studio. A wide range of commissions followed, including his famous windows at Coventry Cathedral, with Keith New and Geoffrey Clarke, which established his reputation. Lee was also a teacher both formally at the Royal College of Art, and in his studio to a succession of assistants. He was notable in acknowledging the contribution of his assistants by including their initials on windows, along with his own.

Other comments

Lawrence Lee was assisted in the making of the window by Janet Christopherson.

The east window contains a fine and instantly recognisable Tree of Jess by Ninian Comper (1934), but rather more rare is a north nave aisle window of St Luke by M H Cuthbert Atchley of Bristol (1929).